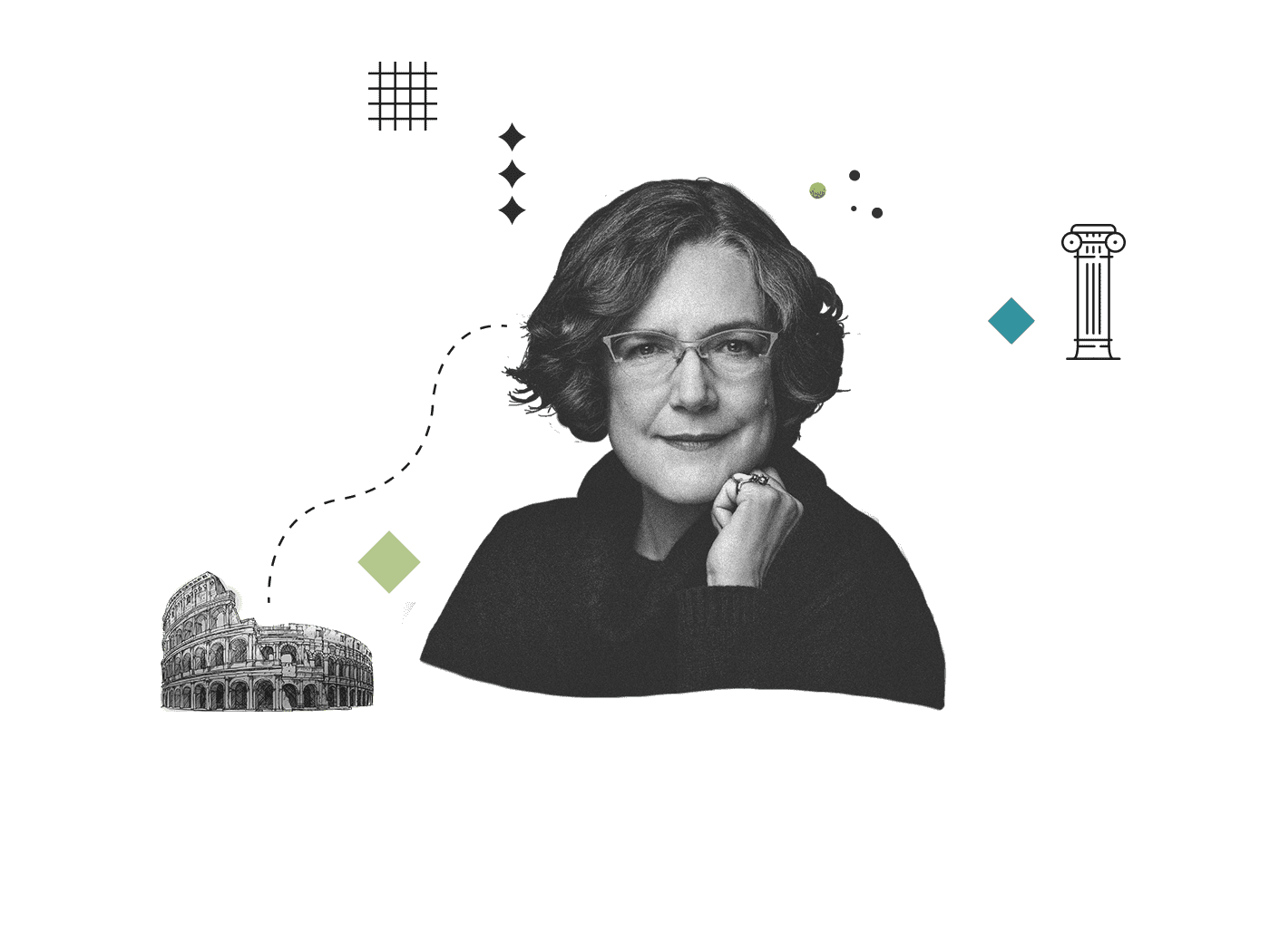

Ingrid Rowland

School of Architecture

Professor, Rome

Though Ingrid Rowland’s father is a Nobel laureate scientist who alerted the world to the depletion of the ozone layer, her favorite story of parental influence on her career as a classics scholar concerns her mother.

After Rowland had begun to write for the New York Review of Books, her editor picked a picture for a story about the University of Chicago. By chance, it featured Rowland’s mother, who at age 15 had been plucked from a suburban neighborhood for a scholarship at the nearby institution, with its pioneering program of Great Books.

“Learning new things is still completely compelling, I guess curiosity never dies.”

“She’s sitting at an oval table that I knew really well because I taught the same course at the same table years later,” Rowland says. “She has the same Herodotus book that I’d grown up with.

“She is a person of absolute principle, including the principle of liberal education.”

While Rowland’s mother gave up work to raise children in a bygone era, the daughter continued down the academic path because it offered the opportunity to study everything.

Rowland’s career has been a ceaseless pursuit of freedom to explore whatever topic captures her insatiable curiosity. It’s why she chose academia, why she pursued the classics and why she now describes herself as a writer based in Rome. In short, she’s a true Renaissance woman.

“I often simply say that I’m a writer,” she says. “Sometimes I find that’s easier, because you get to cover all sorts of topics as a writer and no one thinks it’s odd. That way, you get a total freedom that you don’t get if you restrict yourself to a discipline. Being a writer is just a great cover-all.”

The way Rowland, who holds positions at Notre Dame in the School of Architecture and the Departments of History, Classics and Art History, came to write for the New York Review of Books reveals the ridiculously wide range of her intellectual pursuits.

Robert Silvers, the Review’s founder and longtime editor, liked a piece Rowland had written in 1994 about a Paris exhibition on “The Etruscans and Europe.” Feeling exuberant, she had experimented in a thoughtful but non-academic style, moving easily from what it meant to be European to the political forces then breaking apart the former Yugoslavia.

“At the very end, I compared an Etruscan magnate to J.R. Ewing in [the TV show] ‘Dallas’ and said something about how the Etruscans were the Texans of the ancient world,” she recalls.

Silvers loved her wit, range of thought and clear style. Rowland has since written more than 60 reviews, ranging from art exhibits on theologian Martin Luther to a book on Baroque architecture in Rome to the earliest photographs of the ancient Syrian city of Palmyra. Some of these articles have expanded into her more than dozen book projects.

Rowland grew up as the academic equivalent of an army brat, born in Princeton and moving to Kansas and Irvine, California, with sabbatical interludes in Germany and Vienna. She won science awards in high school and planned to follow her father’s footsteps. She recalled digging with the Boy Scouts at Native American sites in California.

“I really thought I’d do scientific archeology,” she says. “I rose to become the president of my Explorer post, even though girls weren’t supposed to be there.”

Notre Dame Art and Architecture Historian Ingrid Rowland

My Dad Said “Be Yourself,” but Mom Said, “Roll With the Punches”

Her father, however, reminded her that she could write better than she could calculate. The chemist who helped discover that chlorofluorocarbons deplete the ozone layer was an “aspiring writer” himself, she says, having once submitted an article to Collier’s magazine. Luckily, it wasn’t accepted, or “the world probably would have lost a scientist.”

At Pomona College, a charismatic classics teacher, Harry Carroll, littered his lectures with Greek words and ancient stories. Rowland was hooked. She went on to earn her master’s and doctoral degrees in Greek literature and classical archaeology at Bryn Mawr College.

Her love affair with Rome began during brief visits as a child, but it blossomed when she discovered Baroque architecture in graduate school.

“In the Roman Forum you know that Cicero really did speak there, and you know Julius Caesar saw some of the same buildings we see today,” she says. “That’s very exciting because sometimes you can attach human beings to these structures, and that makes them much more alive for me.”

She gradually moved from the classics to Renaissance studies. In graduate school, when she was supposed to be writing about Greek heroes, she found herself sneaking into the Vatican library to read instead about Raphael and his patrons.

“For much of my career, following the straight path would just have left me banging my head into the glass ceiling,” she says. “I’ve usually gone around the side, pursuing what I want without expecting any degree of personal success.”

She began teaching in 1979 at the Saint Mary’s College Rome Program, the first stop in a career where all roads led back to Rome. Highlights include four years in the classics department at UCLA and a decade in the art history department at University of Chicago before the cold winters drove her back to Rome again in 2001. Now at Notre Dame, with a position split between architecture and history, she spends one of every four semesters back on campus.

Rowland’s experience with the New York Review of Books has led to a focus on writing for the general public as well as specialized studies for academic publishers, including the Vatican Library. That and teaching, she says, have sharpened the clarity of her writing without limiting her range of topics.

Upcoming projects include a book on the painter Caravaggio and a study of influential ancient women, including Plato’s sister and the person, presumably his wife, who complained to the Roman architect Vitruvius that the new temple to Julius Caesar had columns too narrowly spaced for two matrons to walk between them arm in arm.

“Learning new things is still completely compelling,” she says. “I guess curiosity never dies.”