Malgorzata Dobrowolska-Furdyna

College of Science

Associate Dean for Undergraduate Studies

Physics got to Malgorzata “Margaret” Dobrowolska-Furdyna’s head twice.

The first time, she was a high school student in Poland. As a lover of mathematics, Dobrowolska-Furdyna realized that physics was fun. She loves to solve puzzles, and she has the ability to put together parts and pieces and make sense of them.

“Solving physics problems came easily to me, and then to my dismay, not to my classmates. But that goes to your head, because then you think that you’re smart,” she says.

“It’s vital that women’s ideas and experiences equally influence the design and implementation of the innovations that shape our future societies.”

The second time, she had been accepted as one of 300 students in the physics department at Warsaw University. At the end of the year, only 100 remained. And though Dobrowolska-Furdyna was among that fortunate third, the rigor of the program became daunting. Physics was no longer as easy as she thought it was.

“And that also goes to your head, and you begin to think, ‘I’m probably not that smart after all,’ because it’s easy for this guy and that guy … and that’s a feeling I still remember,” said Dobrowolska-Furdyna, now the Rev. John Cardinal O’Hara, C.S.C., Professor of Physics and associate dean for undergraduate studies in the College of Science.

Of course, with time physics became easier again and research became exciting, but her memory of early struggle has fueled her passion for helping students improve their skills enough to remain in science. She encourages students through her position as associate dean, and through her co-development of a new program, Science and Engineering Scholars, designed to assist students who enter Notre Dame without a rigorous high school foundation in calculus and chemistry.

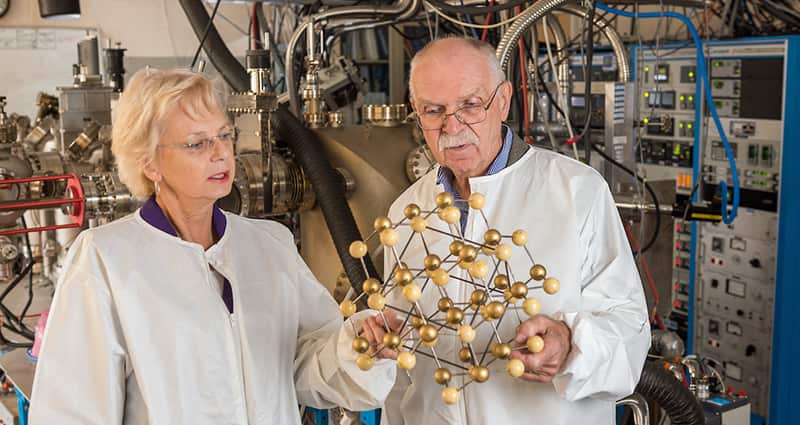

After graduating from Warsaw University, Dobrowolska-Furdyna earned her doctoral degree from the Institute of Physics, Polish Academy of Sciences, and planned to work in academia. She left Poland for two years to work at Purdue University in the condensed matter physics laboratory with physicist Jacek Furdyna. After her postdoctoral research was complete, she worked in Poland for two years as an assistant professor, and returned to the U.S. to marry Furdyna. Both came to Notre Dame in 1987 to set up their laboratories, and Dobrowolska-Furdyna began her research on optical properties of man-made magnetic semiconductors.

Thirty years of molecular beam epitaxy stimulates international collaborations

Lyubov Titova, now an assistant professor of physics and assistant professor of chemical engineering at Worcester Polytechnic Institute in Massachusetts, worked in Dobrowolska-Furdyna’s lab in 1999 and defended her doctoral thesis under her guidance in 2004. She remembers the highly collaborative nature of Dobrowolska-Furdyna’s lab.

“This was definitely a right fit for me as it allowed me to develop skills and confidence,” Titova said. “She was an excellent research adviser as well as a supportive mentor who taught me a wide range of skills, from how to operate a superconducting magnet to how to develop a clear and engaging conference presentation.”

In 2013 Dobrowolska-Furdyna published a paper in Nature Materials that answered a question many researchers in the field of magnetic semiconductors had pondered: How was magnetism occurring in a manganese-based type of superconductor? After performing several experiments, she and collaborators eliminated several possible mechanisms and arrived at an answer that she believes solved the puzzle. The important discovery had taken several years of research to solve, and after she completed the paper, Dobrowolska-Furdyna felt like she needed a new challenge, as her heart had already started turning toward mentoring.

That’s when the former dean of the College of Science, Gregory Crawford, approached her about taking on the role of associate dean for undergraduate studies. And a lightbulb went on. “I kind of knew that maybe this was the thing I was looking for, and it was,” she says. “It gives me a lot of satisfaction, being able to make a real difference in this many students’ lives.”

Dobrowolska-Furdyna enjoys talking with and mentoring students in her role as associate dean. In her office is a crystal apple given to her by a student who decided to remain enrolled at Notre Dame based on her encouragement. But for years she wanted to do more for students who came to the University slightly underprepared, through no fault of their own. That’s when she partnered with Mary Galvin, the William K. Warren Foundation Dean of the College of Science, who also felt strongly about finding a way to assist and retain these motivated students. Together, and with other professors and a partnership with the College of Engineering, they brought the Science and Engineering Scholars program to fruition in 2018.

The program offers an online, six-week summer refresher course to review pre-calculus topics, along with special small sections of introductory chemistry and calculus classes. A study-skills course is attached to the chemistry course to provide additional practice, and students receive mentoring and continuing academic support throughout their first year. Forty-five students were accepted into the program for this academic year, and Dobrowolska-Furdyna hopes to increase that number for next year.

“It is my passion at this point,” she said.

Because she attended college in Poland, Dobrowolska-Furdyna’s experience was different than it is in the United States — half of each of her physics classes were composed of women, compared with a much smaller percentage here. But she still felt the “need” to be better than the men in order to compete, so encouraging women to pursue physics and science is another of Dobrowolska-Furdyna’s priorities. As a physicist who researches ways semiconductors can be improved, she sees technology as a way to both inspire and help girls in science careers.

“It’s vital that women’s ideas and experiences equally influence the design and implementation of the innovations that shape our future societies,” she said. “We need to start girls early, so they will later use their skills and imagination to create technology solutions to issues that matter most to them.”

Current technlogies, such as basic texting, can improve maternal and child health in rural communities, or in documenting domestic violence, Dobrowolska-Furdyna noted. “We just need to develop more of these technologies that will help empower women,” she said.

Titova recalls that that in addition to being an encouraging force in the physics department, Dobrowolska-Furdyna seemed to easily integrate her roles as a scientist, teacher and parent to son, Michael. Her example was not lost on Titova, who has two children of her own. She is following her mentor’s example by serving as a Luce Mentor to undergraduate women in physics through Girls Inc., a STEM and leadership program for high school students.

“Having her as an adviser and role model certainly reinforced the idea that it is possible for women in science to achieve work-life balance,” said Titova, who will know in early March whether she has been granted tenure.

And after a long career of conducting research, teaching and mentoring, Dobrowolska-Furdyna is pleased to hear about the continued success of her former students. While research has been a foundational part of her career, she is happy to have spent her most recent years with even more of a focus on mentorship.

“My impact on the world is much bigger with educating these students,” she said.